Consciousness in Humans and Elsewhere

Barry Blumberg, Ph.D.

page 3 of 4

An epidemic of HBV infection was reported in Swedish orienteers. This is an active sport in which contestants race through an  outdoor course with a map, compass, and a series of check points through which they may pass. The virus was transmitted when contestants ran through brush and undergrowth. They could wash off their legs at the check points, often using the same basin of water which could serve as a vehicle of transmission. In addition, small amounts of blood remained on the brush with which successive runners often came into contact. Apparently, these small exchanges of blood were sufficient to transfer the virus from infected to uninfected persons.

outdoor course with a map, compass, and a series of check points through which they may pass. The virus was transmitted when contestants ran through brush and undergrowth. They could wash off their legs at the check points, often using the same basin of water which could serve as a vehicle of transmission. In addition, small amounts of blood remained on the brush with which successive runners often came into contact. Apparently, these small exchanges of blood were sufficient to transfer the virus from infected to uninfected persons.

Thus, in addition to the biological functions associated with procreation, the virus has also managed to adapt to common social practices for its transmission. It can even adapt to parochial activities.

HBV has had a long time to develop these adaptations. HBV and related organisms with high homologies (hepadnaviruses) have been found in many of the species in which they have been sought. It is likely that even more species will be found to be infected as the numbers tested increases.

The use of the vaccine that we invented in 1969 and that has been widely used since the 1980s has thwarted most of these means of transmission. Will the virus find other mechanisms for transmission that are not prevented by the vaccine?

The virus has also adapted itself to the immune system of its host in several ingenious ways. As already noted, in order to be transmitted effectively, the virus should remain in the peripheral blood at relatively high titers so that is available to be transmitted by the means discussed above. It remains in the liver and other cells where it can replicate, infect other cells, and enter the blood stream.

The virus can modify the immune system of the host so that it does not recognize the infected cell as containing foreign elements and therefore the host is ineffective at destroying the infected cells and ridding itself of the infection. Research over the past decades has increased the understanding of many of these mechanisms that are important for developing new treatments and preventive methods. The following is a description of a few of these mechanisms.

HBV enters the liver (and other) cells of its host where it can take over the capabilities of the host cell in order to replicate and infect other cells and enter the blood stream. In time, it may integrate into the host genome, including possibly the germ cells, and it can then be transmitted to subsequent generations. The host cells produce the whole replicating virus and, in addition, large numbers of particles that contain only the surface antigen (HBsAg). These can bind to the antibody produced by the host (anti-HBs) and prevent the host antibody from immobilizing the whole virus that can then go on to replicate and infect others. This is another example of the teleological explanation.

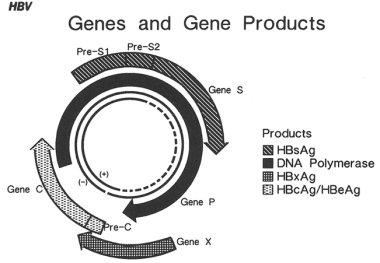

Another ingenious mechanism is shown by the protein produced by the C reading frame, shown in Figure 3.

Image 3: Genes and Gene Products of HBV

The reading frame has two start points. The first results in a protein that is larger than the protein generated from the second start codon, but they both share much of the antigenicity of the C protein. The smaller protein can leave the cell, interact with the host immune system and “tolerize” the host, that is, make the host act as if the C protein is not foreign. As a consequence, when the larger C protein is expressed on the surface of the liver cell, the host immune system will not attack it and the infected cell will remain in the host and continue to produce HBV. This serves the “goal” of the virus to remain in the host, producing high titers of it, and increases its probability of transmission to others.

1 2 3 4 Next Page>